The 'impact' of climate writing

The problem begins simply enough. A journalist finds a word that seems to fit almost everything. It might be "crisis", "pivot" or the ever-convenient "impact". It's concise, authoritative, and headline-friendly. It appears once, then again, and soon it begins to dominate the page. Before long, an entire publication can sound as though it has adopted a single favourite term to describe too many things about the world.

This overuse isn't necessarily misuse. The word may be entirely correct in the context. The issue lies in the excess. When a word is used repeatedly, it begins to lose its freshness and force. What might have seemed efficient at first can become habitual, producing monotony and weakening the overall effect of the writing.

The writing of good journalism depends on proportion and variation. Language must move with rhythm and a modulation, and not be mechanical. The overuse of a single word can flatten that rhythm, producing prose that feels tired and indistinct. (The only exception might be repetition that serves or is served by the narrative.) Even strong ideas can lose their vitality when expressed in language that repeats itself too much.

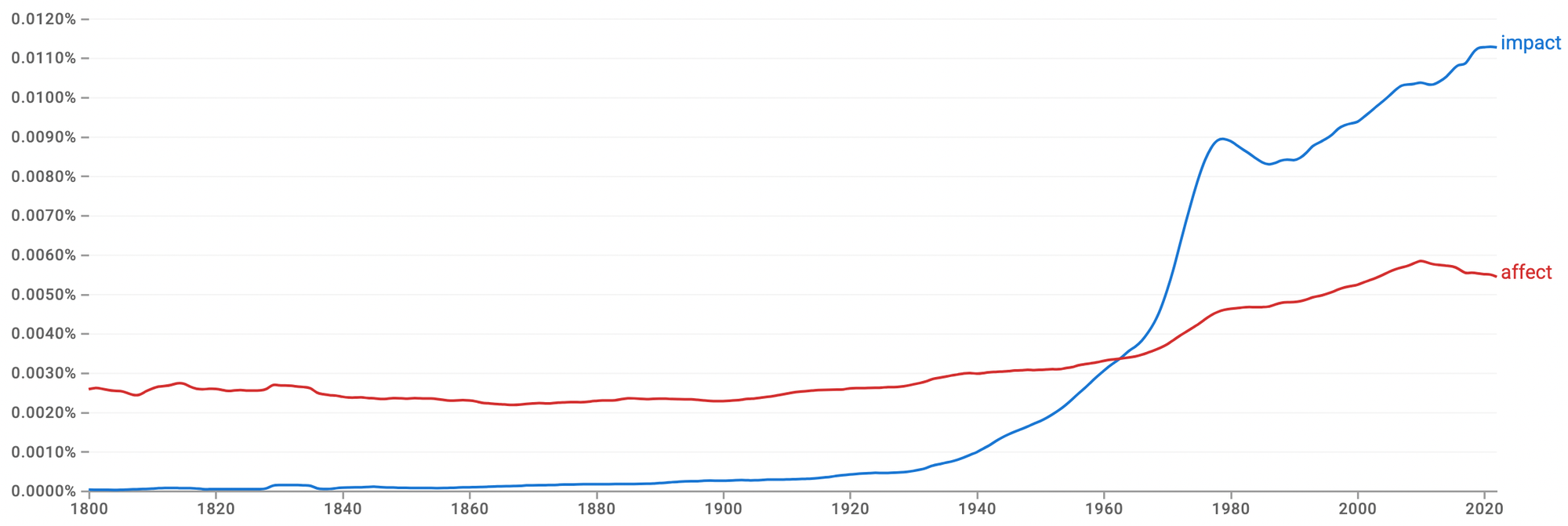

A journalist who relies too heavily on one word also risks blunting the edge. Consider, for example, the widespread use of the word 'impact'. It was once a straightforward noun referring to a collision or perhaps a decisive effect. Now it appears in nearly every context — "social impact", "economic impact", "climate impact", "emotional impact" — and has as a result been deprived of the sense of force it once had.

Here are some examples from articles published in journalistic outlets worldwide:

"But our emissions will have even more lasting geologic impacts…"

"… the impact of concentrated private wealth on extreme climate events"

"… recognising the environmental impact of war is crucial"

"Is the pollution of the past decades having an impact on the present?"

"… protect the world’s people from the growing impacts of the climate crisis"

"It warned that the impact of these emissions was worsened by deforestation"

"… the multi-layered economic impacts of climate change…"

"Volcanoes can impact climate by emitting carbon dioxide…"

"Owners of capital could be held accountable for climate impacts…"

The repetition is not grammatically incorrect but it is stylistically exhausting. The word appears so often that it ceases to register as information. The phrase "have an impact" substitutes for a range of more descriptive verbs — including "affect", "alter", "strain", "improve", "damage" or "transform" — each of which could convey a clearer sense of what is happening.

The overuse of 'impact' is not deliberate carelessness but perhaps linguistic habit. When a journalist defaults to the same word each time, the choice gives way to routine, which could be justified if the journalist is short of time and they believe conveying a 'minimum' of meaning suffices. Yet routine can habituate unthinking writing and a convenient way to snap out of it might be to reach for varied language. Whether in the writer's mind or in the reader's, it forces attentiveness and deliberate selection.

Repetition also affects how readers perceive and process information. When a word appears too often, readers can become desensitised to it. The first use may carry weight; the tenth does not. Overuse creates familiarity and familiarity dulls impact.

In climate journalism, the overuse of 'impact' also carries particular risks because the word lies at the centre of how environmental change is communicated to people. Articles describing "the impacts of global warming", "the impact of rising temperatures", and "climate impacts on agriculture" appear daily across major outlets. The problem is not that these uses are inaccurate — climate change does indeed have profound effects — but that banking on one word can trample a complex reality.

When every phenomenon, from coastal erosion to species extinction to heat stress, is ushered within the general label of "climate impacts", the distinctions blur. Readers may no longer register the specificity of events or the different scales of urgency. Instead of recognising that a drought displaces people in one region while ocean acidification erodes livelihoods in another, they encounter both as part of an undifferentiated category. The result is a sense that everything is an "impact" and that therefore nothing is truly distinct or new.

Over time, such habitual phrasing can also weaken emotional and cognitive engagement. The first few uses of 'impact' may convey seriousness; by the hundredth, however, it could have become background noise. When audiences repeatedly read that communities are "impacted" by climate change, the word no longer evokes the magnitude of what is at stake. What should communicate disruption or harm could instead normalise the extraordinary scale of the issue.

This desensitisation has implications beyond style. Public understanding of climate change depends heavily on how it is framed. If coverage repeatedly invokes 'impact' without variation, it risks promoting a passive sense of causality, as though impacts simply occur, without agents, causes or systems behind them. The word's neutral meaning also obscures responsibility. Saying "climate change impacts farmers" erases agency while saying "changing rainfall patterns have cut yields" or "policy failures are forcing farmers to abandon their land" names it.

There are reputational effects as well. For newsrooms that publish frequently on environmental issues, repeating 'impact' can suggest that the reporting is formulaic, instead of using language that better captures new particularities. Readers in turn may perceive such coverage to be less rigorous or less insightful.

Finally, the intellectual cost mirrors the linguistic one. The word 'impact' once denoted a clear and physical event, one object striking another. But in climate journalism it has become shorthand for almost any outcome, in turn influencing how writers and readers think about the climate itself: less as a system of interacting causes and effects and more as a vague sequence of consequences. Restoring precise language by specifying what kind of change is occurring can thus help restore analytical clarity as well.

Taken together, in the context of climate journalism, restraint and variation are matters of style as well as of responsibility. Climate journalism is the publics' primary interface with scientific understanding and global policy debates. Precise language can help preserve precise thinking, which in turn can support the clarity and urgency effective climate communication demands.